Where It All Began

After moving to New York, I have been reunited with my cookery books. It reminded me of how I was first drawn to cookery as a child. Watching my mother in the kitchen.

This week, the cardboard boxes that have been holding my books for the last year, emerged from storage. As I stripped back the tape, my heart raced and eyes widened to remember so many old friends. I have had to cull a huge number but the stalwarts—and some new acquaintances—have come for the ride. Along with the literary heroes and favourite childhood stories came my cookery books. The aroma of many kitchens past lingering across their pages. Smudges and oily stains marking the favourites as my fingers eagerly search through the memories held within.

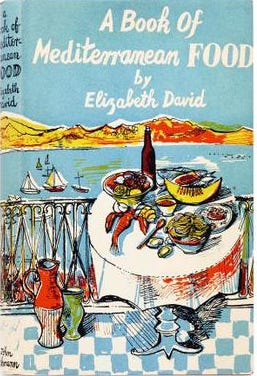

Cooking began with my mother, from whom I acquired an instinct for ingredients, the way others learn music. Watching her in the kitchen fascinated me. And it was a place where we seemed to hold truce. She devoured the work of Elizabeth David, the food writer who coaxed post-war Britain out of pies-and-pudding into the fresh Mediterranean flavours of France and Italy. Move over hot-pot and spotted dick and welcome poulet estragon and mousse au chocolat. Olive oil and salty anchovies appeared like contraband treasures. Pasta and risotto–once exotic and mildly alarming to tweedy county folk raised on nursery food–appeared on menus.

Through David and other writers who had ventured across the English Channel, British cooking slowly transformed. My mother somehow coerced my father’s devotion to gamey roasts and heavy puddings to include some more continental tastes. Salad was no longer hunks of cheese and ham served with slices of cucumber and tomato but bowls of herbs and tender green leaves dressed with the silkiest dressings and served with ripe cheeses, rinds wafting with sour wine. Soups reached beyond heavy broths to clarified bouillons. We had caramelised tartes and crisp quiches with flouncy pastries that flaked with foreign elegance, richly fragrant daubes cooked for hours would emerge steaming from the old stove. And ragu bolognese served with slippery spaghetti slurped up noisily—accompanied by much giggling—through the gap in my front teeth. Thanks to this culinary pioneering, suppers were no longer always served in rigid courses, but placed at the centre of the table to be reached for, shared, maybe dipped with a baguette bought from the French bakery on a visit to the city.

When she was in the mood to cook, I would be despatched by my mother to the kitchen garden with instructions to gather what she needed for that day. Surrounded by orchards of apples, pears and plums, it was a square half acre of bounty, staked and barricaded against rabbits, hare and deer. Beneath the nets, neat lines of vegetables were supported with wires, canes and clay pots; as the weather warmed there were peas and beans clambering their way along hazel twigs, neat rows of spinach, potatoes and onions, and blousy lettuces on long raised beds under glass cloches. When these had all but died out, winter brought cabbages, broccoli and Brussels sprouts. A far less joyful time. I would reluctantly venture to the wasteland, my boots encrusted with clods of heavy mud, fingertips and earlobes freezing in the hoar frost. After I sought sanctuary in the heated greenhouses, where the rubbery sweetness of the fig trees still lingered but here there was nothing to scavenge for a small, greedy boy. The apple store held the last scent of autumn, where the fruit sat in rows on wooden palates, gazing out like the rosy faces of children. Beneath beetroots and carrots slumbered in sandboxes. But these pleasures dwindled by midwinter as the stink of rot began to spread among the apples.

In contrast, summer really was a world of temptation: thick hedges of raspberry canes, ruby strawberries nestling on a bed of straw, gooseberry and currant bushes heavy with fruit. It was all perfectly ordered. Box hedging marked the pathways and sweet peas and cornflowers snaked the boundaries between the beds. My juice stained hands ran through the fragrant herbs that thrust themselves swaying on to the pathways; parsley, tarragon, marjoram, chives, chervil and everywhere mint in all of its many guises.

That early love of ingredients never left me. It still shapes the way I cook, ruled by instinct and imagination. I’ve always believed that confident cooks share two things— they know their kitchens, and they know their ingredients. When you understand what you’re holding in your hands and know what to do with it, you don’t have to follow instructions. You respond to what you have. You trust your instincts. I suppose, it is more or less how I have lived my life too.

My mother cooked whatever was seasonal, or whatever irresistible produce the local grocer could provide. Her pantry was full of ingredients she loved. I still shop and cook the same way. What’s fresh, what’s interesting, what sparks something in my imagination—that’s what goes in the basket. I am a compulsive collector of spices, ferments, and exotic condiments. Filling every corner with surprises that reveal themselves. My fridge is a treasure trove. Life wouldn’t be complete without a fine vintage marmalade or some pickled walnuts winking down from the kitchen shelf. You’ll have your own favourite titbits. If you can imagine yourself unscrewing a lid and poking a finger in to fish out a mouthful of something mouth-watering, then make sure it’s hiding somewhere. These are what tell the story of your cooking and build your love of the kitchen. For a cook, as Elizabeth David wrote, “everyday holds the possibility of a miracle.”

Today I’m making something inspired by spices bought from a spice shop in the East Village—a mesmerising emporium with a bewildering array of jars and dried treasures. These shops are irresistible to me. Like a magician’s cave or an alchemist’s laboratory, they seem to be where the very fumes of life are born. My dish is a Moroccan-leaning stew of beef cheeks with orange zest, ras el hanout, coriander, black limes, juniper berries, and pink peppercorns. Left in the oven for many hours at a low heat, it will be ready tomorrow to accompany a jewelled couscous–made at the last minute–of pomegranate seeds, rose petals, coriander leaves, and pine nuts.

After that, all you need is a table, a few friends, laughter and good conversation.

The best cooking remains the simplest.

The most important ingredient is love.

Beautiful images

Mr Dundas! I’ll have you know that writing about food in such a delicate and tempting way is illegal in many of these United States. But please keep doing it 😝 I loved the description of pulling England from pies and mash. Having grow up in the 70s, everything in the US kitchen focused on “efficiency,” which meant it came from a can or a frozen block. Thus, I thought I hated winter cabbage and Brussels sprouts until I learned to cook them properly. Bravo!